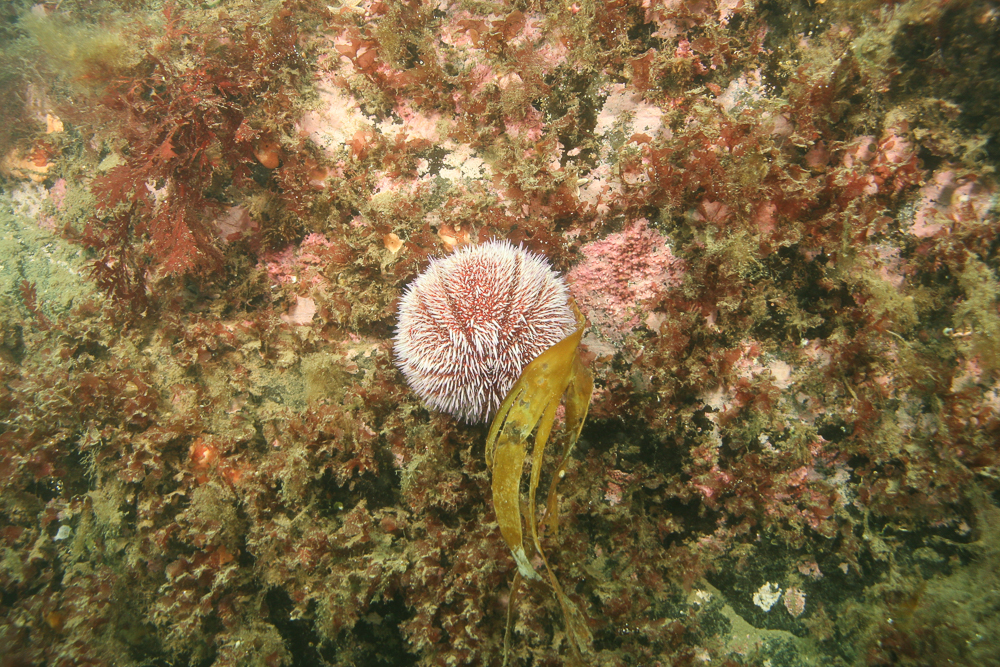

The green sea urchin is common along the kelp front in shallow waters but can be found from the beach down to a depth of several hundred meters, which is an unusually wide depth range. Usually, the green sea urchin crawls slowly along the bottom scavenging on dead kelp and detritus. However, it is known from several localities in the world that it can behave like a locust plague when its population grows too large too quickly. Then, the behaviour changes and it starts climbing up the kelp stipes and eating down the kelp forests.

This has happened in Eyjafjörður. The green sea urchin population expanded rapidly and devoured the kelp, starting at the kelp front (the deepest extent of the kelp forest), and moving up the bottom toward the beach. Behind this advancing multitude, the rock is left bare of kelp, as the urchins chew the algae all the way down to the stone. The green urchin can survive long periods of very little food and gobble up every algal sapling as soon as it begins to grow, thereby stopping the regrowth of the kelp forest.

This is a cause for concern as the kelp forest creates a vital ecosystem for many other species. Cod and saithe juveniles for example use the kelp forest to hide from predators and forage for food. If the kelp forests disappear fewer of them will survive to maturity.

Sea urchins have been fished around Iceland since 1992 and peaked in 1994 with 1500 tonnes harvested. The greatest quantities were harvested in Breiðarfjörður and Húnaflói bays, but considerable quantities were also landed in Eyjafjörður. The market for sea urchin roe collapsed in 1997 and catches have been low since that time. There is no lack of sea urchins and the markets have recovered, but sea urchin roe is a very delicate product and difficult to handle. This is the main reason that the fisheries are currently low.